What We're Learning About Electric Vehicles in the Philippines (And What It Means for Our Future)

Picture this: A delivery rider in Makati swaps his empty battery in 30 seconds and continues his route. Meanwhile, a tricycle driver in Bataan powers up from solar panels on his own roof. This isn't the future—it's happening right now in the Philippines.

After months of watching, analyzing, and building in the Philippine EV space, we're seeing patterns that tell a remarkable story. Not the story policymakers expected, not the story investors assumed, but the story Filipinos are actually writing with their choices, peso by peso, ride by ride.

Here's what we're learning.

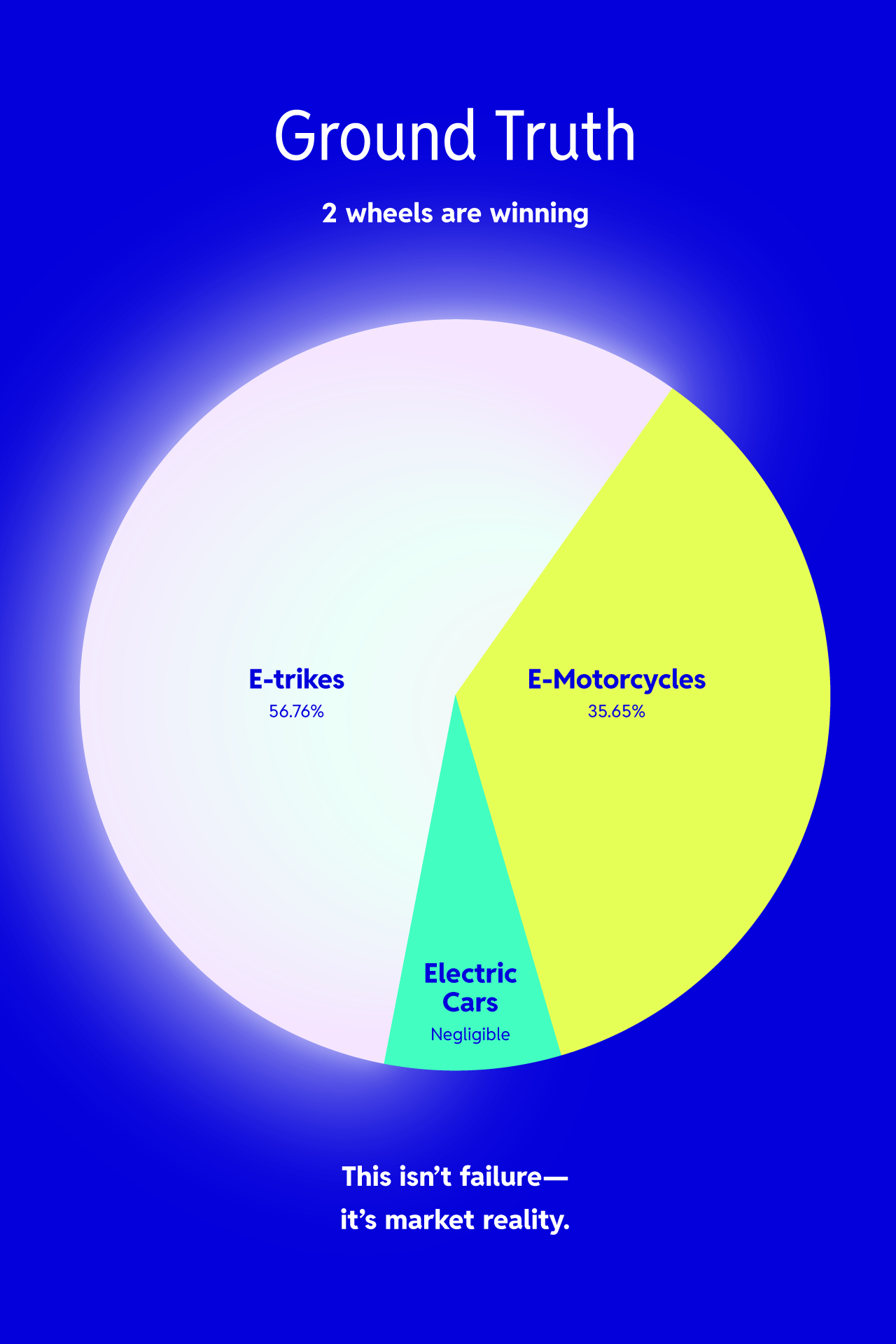

The Ground Truth: Two Wheels Are Winning

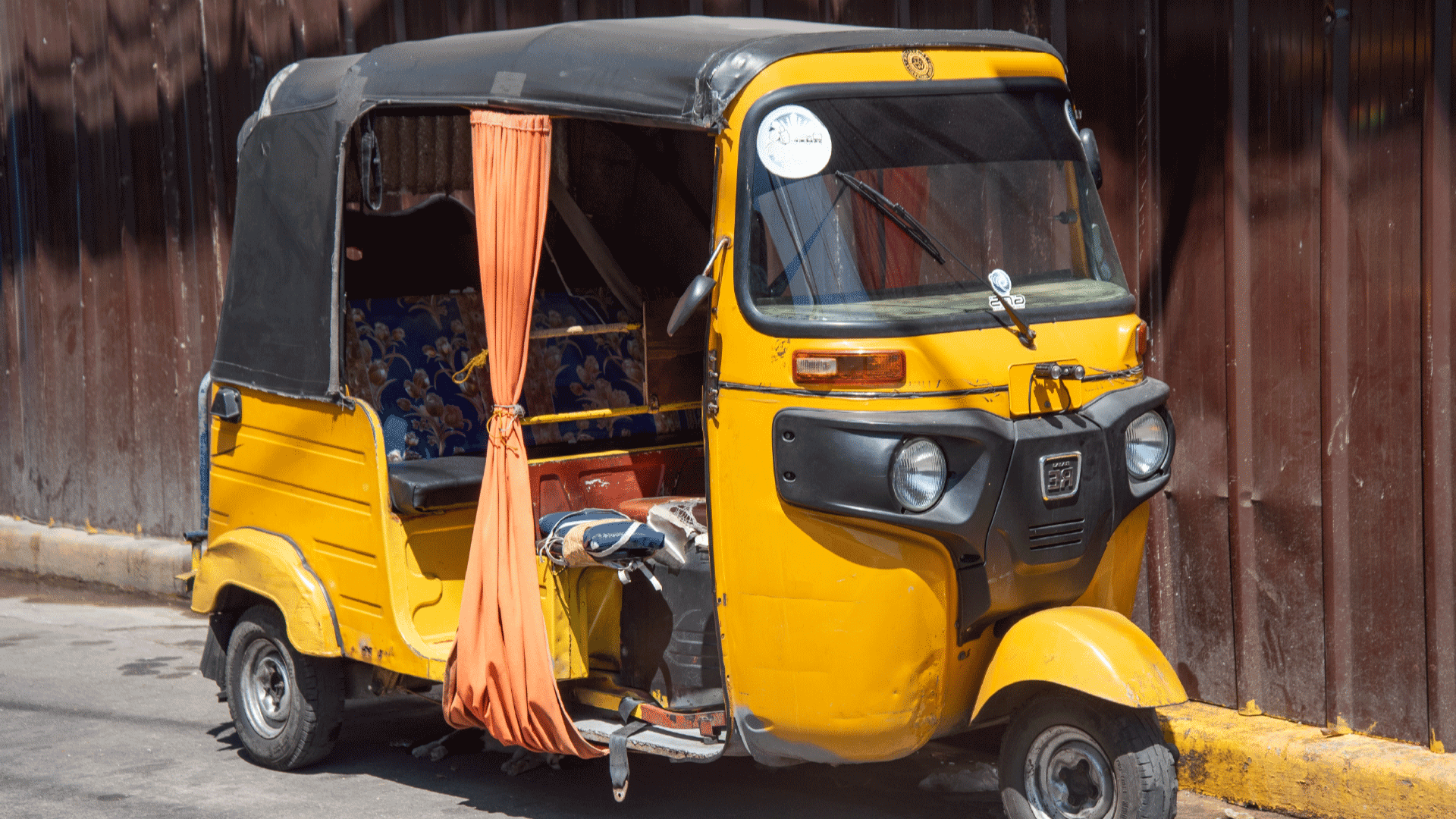

The numbers don't lie, but they do surprise. While global headlines focus on Tesla and luxury EVs, e-trikes comprise 56.76% of registered electric vehicles in the Philippines, followed by e-motorcycles at 35.65%. Four-wheeled electric cars? They're barely a blip.

This isn't a failure of ambition. It's a masterclass in market reality. In a country where EV sales surged from just 214 units in 2019 to 18,690 units in 2024 (an 87-fold increase), Filipinos aren't just adopting electric vehicles. They're defining what electric mobility looks like for the developing world.

The lesson? Electric transformation doesn't have to look like Silicon Valley. Sometimes it looks like a kuya delivering your Grab order on an electric motorcycle, or a tricycle driver who no longer worries about rising gas prices.

Learning #1: Battery Swapping Changes Everything

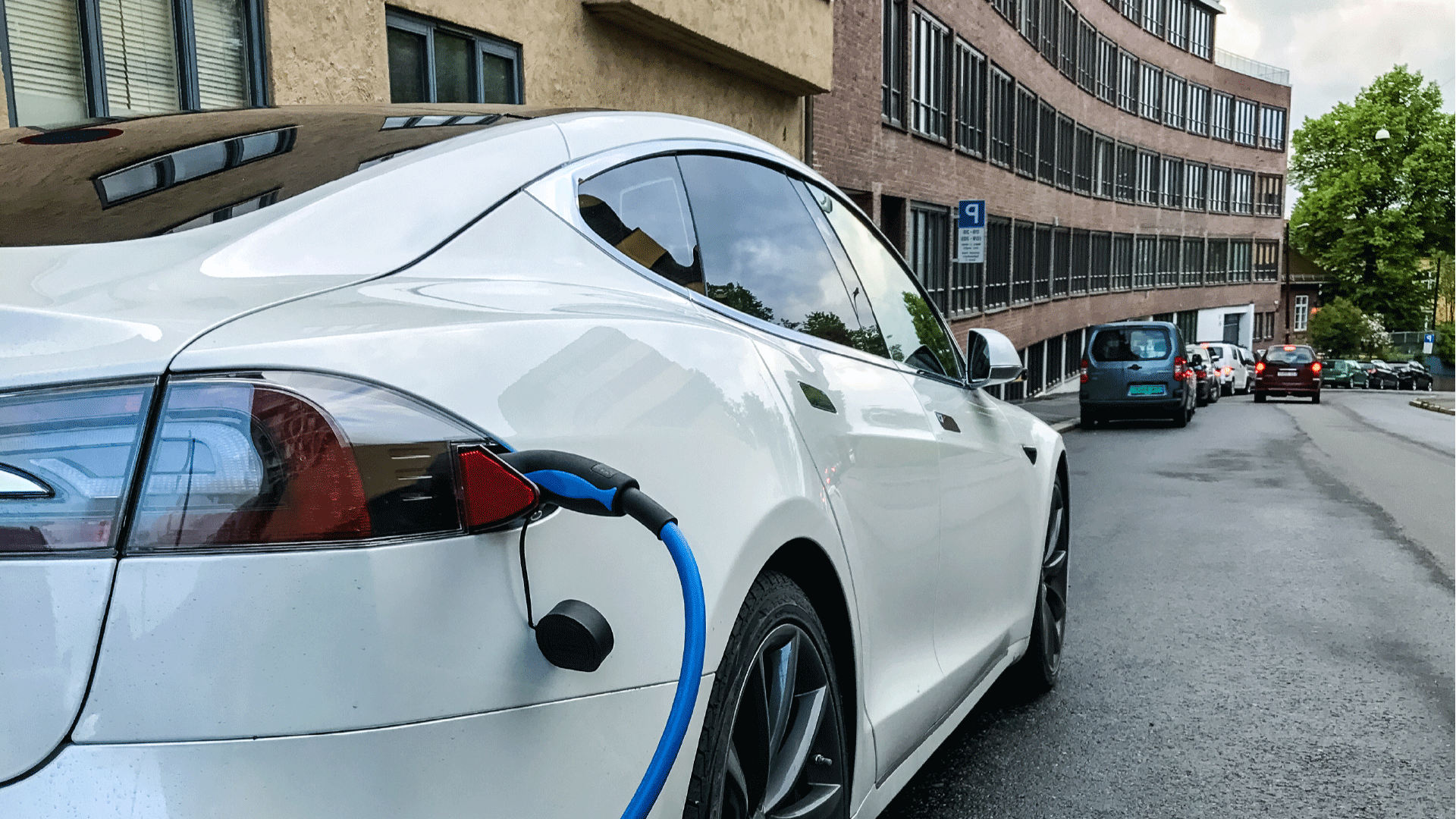

Here's where it gets interesting. While the rest of the world debates charging infrastructure, Filipino entrepreneurs are solving a different problem entirely: time.

Battery swapping, where riders exchange depleted batteries for fully charged ones in seconds, is quietly revolutionizing urban mobility. Startups like Voltai are working to prove that you don't need hours to "refuel" an electric vehicle. You need 30 seconds and a network of swap stations that can fit in a sari-sari store.

This isn't just convenient—it's economically transformative. A delivery rider doesn't own a ₱50,000 battery that depreciates over time. Instead, they pay for energy as they use it, turning a capital expense into an operational one. Suddenly, electric vehicles aren't just for those who can afford the upfront cost.

Taiwan's Gogoro network has over 12,000 battery swap stations serving 500,000+ riders. If the Philippines could achieve even half that density, we'd have solved urban mobility for millions of Filipinos.

Learning #2: Policy Creates Markets (When Done Right)

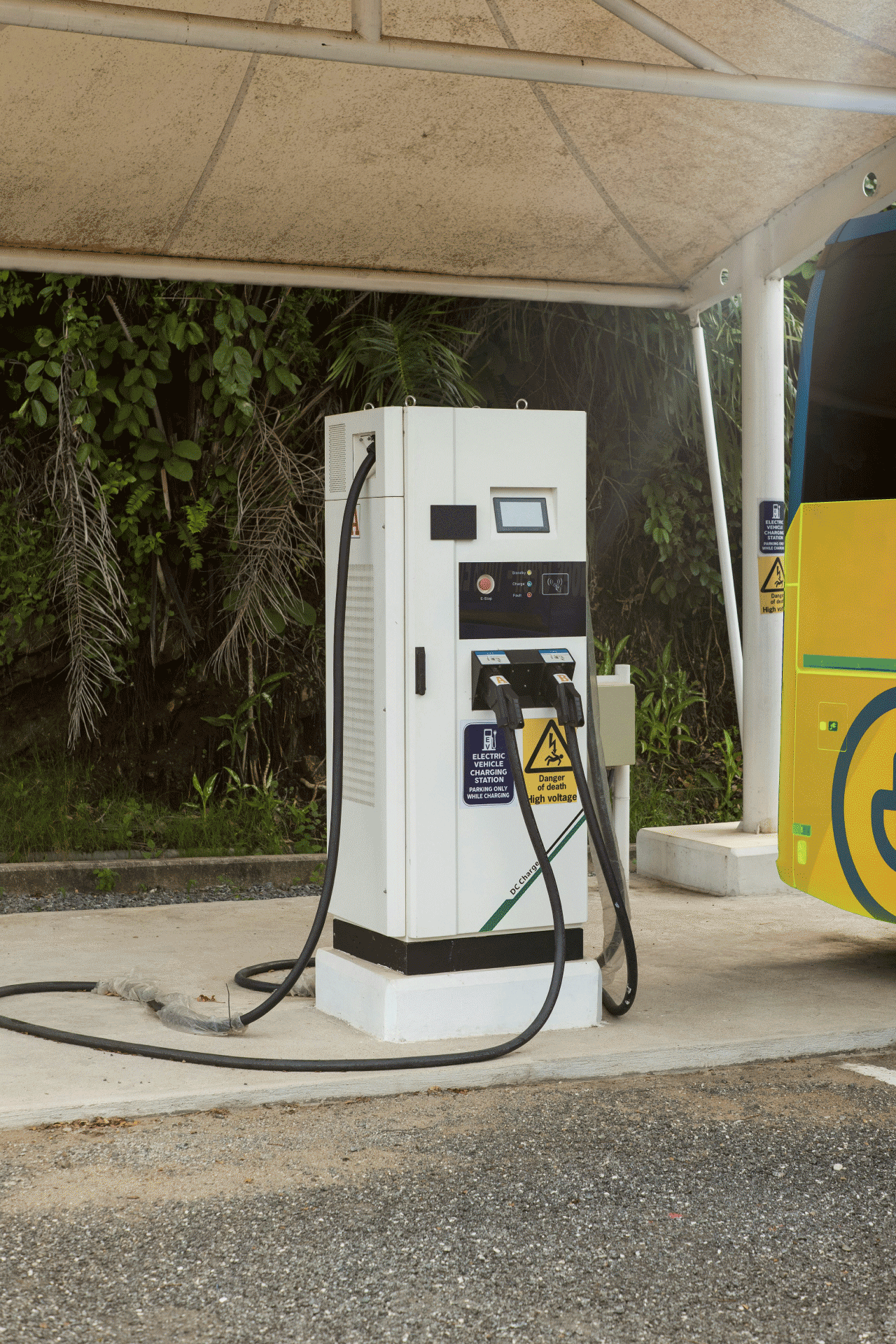

The Electric Vehicle Industry Development Act (EVIDA) of 2022 didn't just create tax incentives—it created permission for an entire industry to exist. Tax breaks, coding exemptions, and mandated charging infrastructure in new buildings sent a clear signal: the Philippines is serious about electric mobility.

But here's what we're learning about policy implementation: national laws create frameworks, but follow-through creates markets. In 2024, the government expanded Executive Order No. 12 to eliminate tariffs on EVs and their components for five years, while NEDA approved expanded zero-tariff rates on battery electric vehicles and components until 2028. The result? Empty EV charging stations in shopping malls are now a thing of the past, with EV owners lining up from early morning to charge their vehicles.

The most effective policies aren't the ones that pick winners and losers. They're the ones that remove barriers and let Filipino ingenuity flourish.

Learning #3: Energy Independence Starts Small

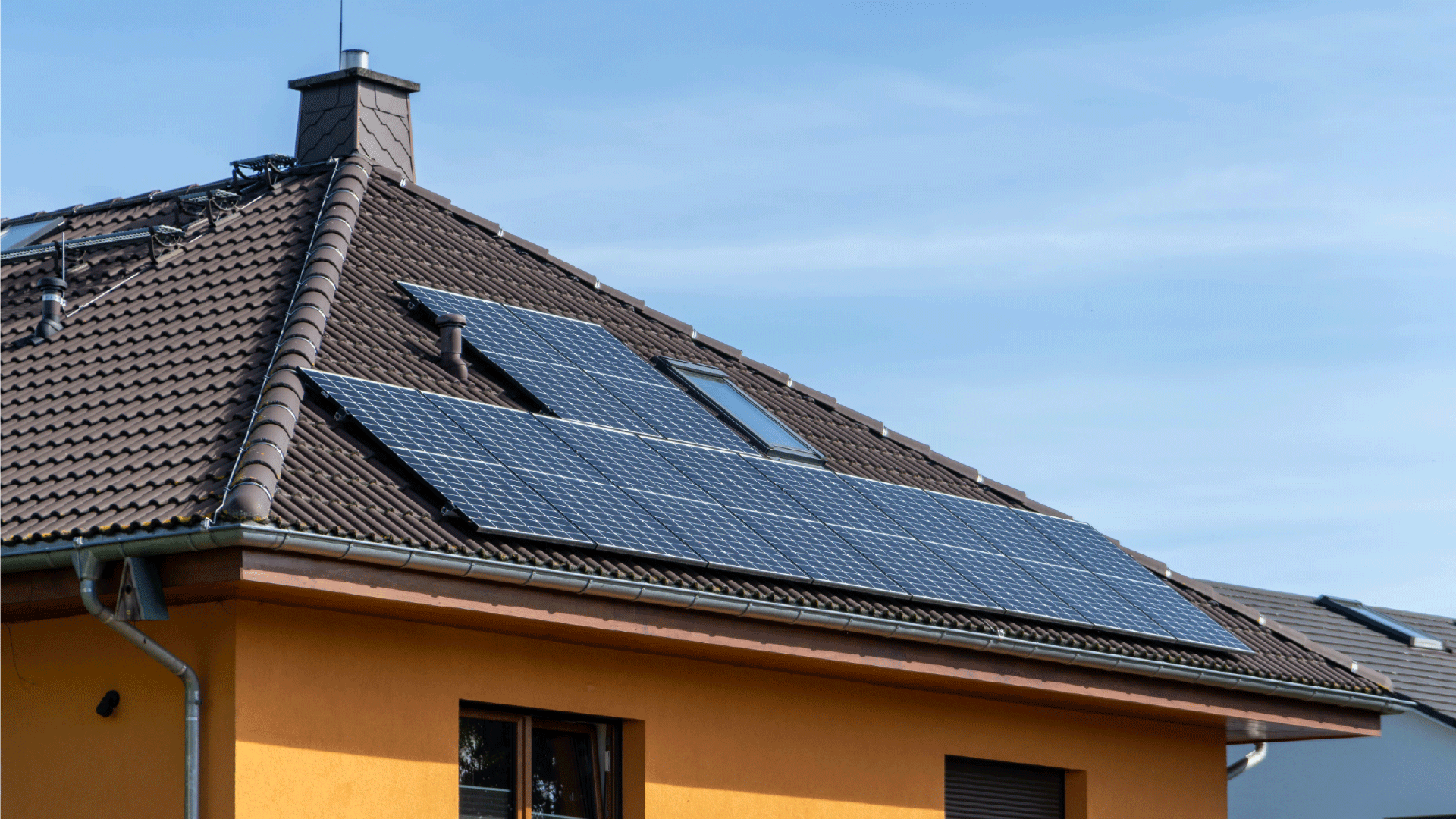

Every electric tricycle powered by rooftop solar panels is a small act of energy independence. Multiply that by thousands, and you have a revolution.

The economics are compelling: gasoline-powered tricycles require US$6 of fuel per 100 kilometers, while e-tricycles need just US$1 worth of electricity—an 83% cost reduction. We're watching drivers who used to spend ₱500 daily on gasoline now power their vehicles for ₱100 worth of electricity, or even less with solar panels.

Despite government missteps (the DOE's ADB-funded e-trike project faced years of delays and was ultimately assessed as "less than successful", and authorities now ban e-trikes from major Metro Manila roads) the market is moving forward. For example, companies like sunE are proving that solar-powered electric mobility works at scale.

The savings don't just stay in drivers' pockets; they stay in the Philippine economy instead of flowing to oil exporters halfway around the world. This is decentralized energy in action. It’s not done through grand infrastructure projects, but through individual choices that add up to national transformation.

The Big "What If": Philippines Goes Full Electric

Imagine the Philippines in 2035, where every jeepney, tricycle, and motorcycle runs electric.

Picture sari-sari stores doubling as battery swap stations, generating income for families while keeping riders moving. Imagine OFW remittances going toward solar panel installations instead of gasoline, turning overseas earnings into permanent energy assets.

In this Philippines, the massive amounts we currently spend on oil imports (over $16 billion annually according to recent DOE reports) stay in the local economy. Manufacturing hubs emerge around battery assembly and electric vehicle production. The country that perfected the jeepney became the innovation center for tropical electric mobility.

This isn't fantasy. Vietnam added over 9 GW of solar capacity in just two years. Thailand is targeting 30% EV adoption by 2030. If our neighbors can move this fast, so can we.

The economic impact would be staggering. The Philippines could create 350,000 renewable energy jobs by 2030, many of them in EV-related industries. More importantly, we'd prove that climate action and economic development aren't opposing forces—they're the same force, directed toward a sustainable future.

The Obstacles We're Learning to Navigate

Of course, it's not all smooth sailing. We're learning about grid capacity constraints as EV adoption accelerates. We're discovering that while battery swapping solves charging time, it requires new business models and regulatory frameworks.

There's also the import dependency challenge. Most batteries and components still come from China and other manufacturing centers. Building local supply chains will take time, investment, and strategic partnerships.

But these aren't insurmountable problems—they're the next set of opportunities. Every challenge we solve for the Philippines creates expertise we can export to other tropical, archipelagic nations facing similar transitions.

Why This Matters Beyond Transportation

What we're learning about EVs isn't just about vehicles. It's about reimagining how a nation powers itself.

Every electric tricycle that charges from solar panels is a small power plant. Every battery swap station that manages energy storage is a node in a smarter grid. Every Filipino who chooses electric mobility is voting for energy independence.

The transportation revolution and the energy revolution aren't separate stories. They're the same story, being written by millions of individual choices that add up to national transformation.

The Future We're Building

The Philippines has natural advantages that most countries don't: abundant renewable energy resources, a skilled workforce, and a proven ability to innovate with limited resources. We're learning that electric vehicles aren't just about replacing gasoline engines—they're about creating entirely new economic opportunities.

We're also learning that the transition doesn't have to wait for perfect infrastructure or complete policy frameworks. It can start with a single electric tricycle, a single battery swap station, a single solar panel on a single roof.

What we're learning isn't just about vehicles. It's about reimagining how a nation of 7,641 islands moves, works, and thrives. The question isn't whether the Philippines will go electric. It's whether we'll lead the transition or follow it.

The evidence suggests we're already leading, one electric kilometer at a time.